Anton Piatigorsky's The Iron Bridge dramatizes small incidents from the teenage years of six brutal 20th-century dictators: Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Mao Tse-Tung, Josef Stalin, Rafael Trujillo, and Adolf Hitler. It's--well, I want to call it a "fun" project, is that OK? perhaps the even less descriptive "interesting"? It's also a bit MFA thesis-y, to be honest. Perfectly competent writing, but little fervor (except in Hitler's off-the-cuff diatribes in "Incensed," but he's also the easiest subject, right?), and a certain predictability to the whole endeavor; suffice to say it didn't knock my socks off. Though I may have been spoiled by the genius of Richard Hughes' characterization of Hitler in The Human Predicament.

Anton Piatigorsky's The Iron Bridge dramatizes small incidents from the teenage years of six brutal 20th-century dictators: Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Mao Tse-Tung, Josef Stalin, Rafael Trujillo, and Adolf Hitler. It's--well, I want to call it a "fun" project, is that OK? perhaps the even less descriptive "interesting"? It's also a bit MFA thesis-y, to be honest. Perfectly competent writing, but little fervor (except in Hitler's off-the-cuff diatribes in "Incensed," but he's also the easiest subject, right?), and a certain predictability to the whole endeavor; suffice to say it didn't knock my socks off. Though I may have been spoiled by the genius of Richard Hughes' characterization of Hitler in The Human Predicament. Limit Vol. 6 (publishes July 23) wraps up the "Mean Girls meets Lord of the Flies manga series I've been devouring since the beginning. I'd worried mid-series that the story would suffer from the marooned girls' discovery that a male classmate survived as well, cause boys ruin everything, but then there was a murder, and paranoia, and red herrings, and I was hooked again. And I found this last volume utterly satisfying and sweet--I may have even shed a few tears.

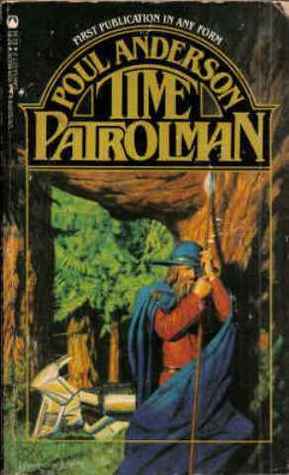

Limit Vol. 6 (publishes July 23) wraps up the "Mean Girls meets Lord of the Flies manga series I've been devouring since the beginning. I'd worried mid-series that the story would suffer from the marooned girls' discovery that a male classmate survived as well, cause boys ruin everything, but then there was a murder, and paranoia, and red herrings, and I was hooked again. And I found this last volume utterly satisfying and sweet--I may have even shed a few tears. Time Patrolman came into my life as a Kickstarter reward, from Ad Astra Books and Coffee in Salina, KS. It's really two novellas rather than a single story: the first, "Ivory, Apes, and Peacocks," takes place in 950 BC in the flourishing Phoenician city of Tyre. Manse Everard has come there to investigate a bomb sent from the future by temporal terrorists unknown; as a member of the Time Patrol--an organization formed to protect the integrity of humanity's history--he must track down the perpetrators, in time as well as space, before they carry out their threat to destroy the whole city, with the millenia of repercussions such a catastrophe would create. It's a fun historical/sci-fi detective story, with a great sense of place.

Time Patrolman came into my life as a Kickstarter reward, from Ad Astra Books and Coffee in Salina, KS. It's really two novellas rather than a single story: the first, "Ivory, Apes, and Peacocks," takes place in 950 BC in the flourishing Phoenician city of Tyre. Manse Everard has come there to investigate a bomb sent from the future by temporal terrorists unknown; as a member of the Time Patrol--an organization formed to protect the integrity of humanity's history--he must track down the perpetrators, in time as well as space, before they carry out their threat to destroy the whole city, with the millenia of repercussions such a catastrophe would create. It's a fun historical/sci-fi detective story, with a great sense of place. Still, I liked the second tale, "The Sorrows of Odin the Goth," much better--its emotionally engaging characters and immersion in the everyday life of ordinary people insignificant to history remind me of Connie Willis's Oxford time-travel stories. Carl Farness is recruited to the Time Patrol as an academic; formerly a professor of Germanic philology, he wants to track down the truth of events among the fourth-century Ostrogoths that gave rise to legends recorded centuries later. But while there, he falls in love, and when Jorith dies in childbirth, he becomes determined to protect his offspring, born 1500 years before him. His entanglement with his own descendants gets him in trouble, of course, but it's not till the very end that he realizes how great the damage he's done, and the one agonizing choice that remains to him to fix things. Sad, beautiful, and complicated (I mean, the tenses alone!).

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of The Iron Bridge and Limit Vol. 6 from Steerforth and Vertical, respectively.)